Energy Resilence As Infrastructure Of Stability

Authors: O. Krishevich, V. Peretyachenko

A global architectural approach to protecting critical systems in an era of systemic failures

ABSTRACT

The global electrical infrastructure is undergoing a phase of systemic stress. In the United States, a significant share of grid assets is operated beyond their originally designed service life — approximately 70% of transmission lines and large-scale equipment are older than 25 years, while the typical design horizon is 40–50 years. Large-scale outages have increased both in frequency and duration over the past two decades. In many developing regions, blackouts are not an exception but part of everyday reality, while hundreds of millions of people still lack access to electricity.

The centralized architecture of power systems (large-scale generation + long-distance transmission + single control points) transforms individual technical or organizational failures into cascading systemic crises, as demonstrated by major outages between 2003 and 2025. On 28 April 2025, a large-scale blackout occurred on the Iberian Peninsula, affecting the entire power systems of Spain and Portugal — a vivid illustration of the structural vulnerability of centralized grids.

Key thesis: the solution is not in the search for an “ideal device.” The solution lies in an architectural paradigm of resilience: decentralized energy nodes, autonomous microgrids with island mode capability, modular sources (renewables + storage + firm/dispatchable sources), elimination of single points of failure (SPOF), and the integration of cybersecurity into system design.

This study analyses: (i) the global context of infrastructure vulnerability, (ii) real-world energy crises of 2023–2025 and their cost, (iii) the social and economic consequences of failures, (iv) architectural principles of resilience, (v) the technological landscape through the lens of TRL logic, (vi) the positioning of solid-state modular solutions of the VENDOR.Max class as an architectural element (rather than a unique “miracle”), and (vii) regulatory evolution toward resilience-by-design in the EU, the United States, and globally.

KEY FINDINGS

- Centralized power systems exhibit structural vulnerability to cascading failures, whereby a single technical or organizational malfunction can lead to systemic consequences.

- Aging grid infrastructure is a significant driver of both increased frequency and duration of outages, particularly under conditions of rising load and increasing operational complexity.

- Energy resilience is achieved through architectural solutions that include distribution, redundancy, and autonomy, rather than through the selection of a single “most efficient” device.

- Solid-state generators of the VENDOR.Max class (TRL 5–6) should be correctly viewed as one element of a microgrid architecture, potentially applicable for covering part of the firm load, subject to further engineering validation.

- The economic assessment of microgrids and autonomous nodes is scenario-based and must account for sensitivity to key parameters: cost of capital, electricity prices, outage frequency, and reliability requirements.

- Regulatory policy in the EU and the United States is consistently shifting toward a resilience-first principle, as reflected in initiatives such as the CER Directive, the European Grids Package, and programs of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Global Challenge: Aging Grids and Uneven Access to Energy

- Architectural Flaw: Why Centralized Grids Are Fragile

- Real Crises: The Cost of Failures 2023–2025

- Social and Economic Consequences of Blackouts

- An Architectural Approach to Resilient Energy

- Technology Landscape and TRL Logic

- Solid-State Systems of the VENDOR.Max Class: Role, Limitations, Ecology

- Modular Architecture: Scaling and Redundancy

- The Economics of Resilience: An Illustrative Model

- Policy and Regulation: Resilience as a New Standard

- Why This Is a Necessity of the Present, Not the Future

- Conclusion and Recommendations

1. GLOBAL CHALLENGE: AGING GRIDS AND UNEVEN ACCESS TO ENERGY

1.1. Aging Infrastructure in Developed Economies

In North America and Europe, a large share of grid assets was constructed in the 1960s–1980s and today operates under load levels and operating regimes that were not originally anticipated.

The situation in the United States (based on public reviews 2024–2025):

- Approximately 70% of transmission lines and large-scale equipment are older than 25 years, whereas the typical design horizon for large transformers is 40–50 years.

- A significant portion of distribution networks is classified as “beyond useful life,” increasing the frequency of failures and emergency repairs.

- The number of major outages (affecting tens of thousands of customers) has increased markedly after 2010 compared to the previous decade.

- The average duration of outages has increased.

According to a U.S. Department of Energy report (July 2025), under a scenario involving the continued retirement of 104 GW of firm capacity and insufficient addition of new firm generation, annual Loss of Load Hours in DOE models may increase from single-digit hours per year today to more than 800 hours per year by 2030 — i.e., approximately a 100-fold increase relative to current levels. This is a scenario-based calculation, not a baseline forecast.

Regulatory bodies and energy ministries observe a consistent trend: without accelerated modernization, increased reserve capacity, and the introduction of more “flexible” grid architectures, the risk of large-scale blackouts will rise toward the early 2030s.

1.2. Developing Markets: Frequent Blackouts and Electrification Deficits

In developing regions, the problem is not only aging infrastructure but also fundamentally insufficient grid capacity, high dependence on weather conditions, and chronic underinvestment in networks.

Global picture:

- Hundreds of millions of people in Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia still live without continuous access to electricity.

- In many countries, the frequency of power outages is measured in dozens of days per year.

- Parts of the economy are forced to rely on diesel generators and informal power sources.

Major events of recent decades:

- 2012 India: outages affecting hundreds of millions of people (one of the largest by population impact).

- 2009 Brazil: large-scale regional outages.

- 2011 Southwestern United States: major regional blackout.

- 2025 Iberian Peninsula: total blackout of the power systems of Spain and Portugal.

In parallel, the number of initiatives by the World Bank, regional development banks, and national governments aimed at financing grid modernization and the deployment of decentralized solutions is increasing.

2. ARCHITECTURAL FLAW: WHY CENTRALIZED GRIDS ARE FRAGILE

2.1. Cascading Failures and the Role of Single Faults

Centralized systems with large generators, long transmission lines, and tightly coupled dispatching are prone to cascading failures: a local problem can trigger a chain reaction.

Mechanics of a centralized system:

- Generation is concentrated in large facilities (thermal, nuclear, hydro).

- Power is transmitted over long distances via high-voltage lines.

- Control and balancing are performed through centralized dispatch.

- The failure of a single component can lead to power flow redistribution and overload of neighboring elements → protection activation → cascade.

Important: in real systems, a cascade is not “one faulty transformer,” but a composition of factors: operating margins, protection settings, inertia/frequency stability, availability of fast reserves, cyber/communication layers, and coordination of intersystem power flows.

Case: Iberian Blackout, 28 April 2025

Facts (based on public sources):

- Date: 28 April 2025, approximately 12:33 CEST.

- Geography: Spain, Portugal; briefly — parts of southwestern France.

- Nature: total blackout of the power systems of Spain and Portugal (event recorded by ENTSO-E).

- Restoration: within hours; in most areas — approximately ~10 hours.

- Disconnected load: public estimates around 31 GW (metrics vary by source).

Consequences: reports indicated tragic incidents potentially linked to the outage (fires caused by candles, carbon monoxide poisoning from generators, disruption of medical services).

Causality: at the time of public materials, the formulation remained “cause under investigation / early analysis.” At the institutional level, it is appropriate to: (i) record the fact, (ii) describe mechanisms as possible / based on early analysis, and (iii) refrain from asserting a root cause as proven in the absence of an official commission report.

Energy incidents of the past decade across different regions of the world demonstrate common elements:

- Line overloads and incorrect sequencing of protection operations.

- Insufficient availability of fast-responding capacity.

- Complexity of coordination among multiple system operators.

- Limited time and incomplete information for decision-making.

2.2. Three Fundamental Vulnerabilities

Vulnerability 1: Weather and Logistics

In many systems, the growing share of solar and wind generation reduces grid “inertia” and makes frequency control more complex without corresponding modernization. At the same time:

- Diesel backup generation depends on fuel logistics and is exposed to price and geopolitical shocks.

- Chemical energy storage systems depend on global supply chains of lithium, cobalt, and other critical materials.

- Digitalization of grids creates a broad attack surface for cyber interference.

Vulnerability 2: Storage Systems — Life-Cycle Constraints

Degradation:

- Li-ion: capacity degradation depends on cycling and temperature.

- Lifespan: typically 10–20+ years, but infrastructure horizons of 40–50 years require a replacement strategy.

End-of-life and environmental footprint:

- Recycling can significantly reduce emissions compared to primary material extraction.

- Requires industrial infrastructure; the processes themselves involve energy consumption and emissions.

Supply-chain geopolitics:

- Cobalt, lithium, nickel, and processing capacities are unevenly distributed.

- Dependence on a limited number of hubs creates strategic risk.

Vulnerability 3: Cyberattacks and Digital Infrastructure

- Legacy assets were often not designed for modern threat environments.

- The IoT layer and DER integration increase the attack surface.

- Coordinated attacks can accelerate the development of cascading events.

Studies on power system cybersecurity show that coordinated attacks on multiple substations and control elements can accelerate cascading failures and complicate restoration.

3. REAL CRISES: THE COST OF FAILURES

3.1. Global Cases (Illustrative Examples)

Italy Blackout (28 September 2003)

- Scale: outage affected more than 55 million people (virtually all of Italy except Sardinia).

- Duration: restoration by region took hours; in some areas — until night or the next restoration stage (time dispersion was significant).

- Macroeconomic damage: in the academic assessment by Schmidthaler & Reichl (2016), damage from Italy 2003 is estimated to exceed €1.15 billion (estimate depends on methodology and loss composition).

India Blackouts (30–31 July 2012)

- 30 July — outage affected more than 400 million people.

- 31 July — a second, larger outage affected approximately 620–670 million people (about half of India’s population and ~9% of the world’s population).

- Power loss / supply disruption: publications cite an estimate of approximately ~32 GW (as “interrupted/affected” capacity) for one of the event days.

- Nature of impacts: transportation shutdowns, water supply disruptions, and transition of some critical facilities to backup power.

Systemic context (United States, annual outage impact)

- According to LBNL estimates (for DOE), total economic losses from power outages in the United States are estimated at approximately $79–80 billion per year (a wide sensitivity range is also reported in various publications).

3.2. Cost of Failures for Critical Infrastructure

Healthcare / Hospitals

- Industry assessments (based on Ponemon studies cited in sector reports) estimate the “typical” damage from a serious power outage incident in a hospital at approximately $690,000 per event (direct and indirect losses).

Data Centers

- In widely cited Ponemon estimates (in industry reviews), the average cost of unplanned data center downtime is approximately $8,851 per minute; with typical incident durations, this rapidly scales to hundreds of thousands of dollars per event.

Section 3 conclusion

Major systemic failures (Italy 2003; India 2012) demonstrate that with durations of hours to days, damages can exceed €1 billion per event in developed economies, while for critical facilities the cost of a single incident is often measured in hundreds of thousands of dollars or more.

4. SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES OF BLACKOUTS

4.1. Critical Infrastructure: Healthcare, Water, Digital Systems

Power supply failures have direct and measurable consequences for critical infrastructure — primarily for healthcare, water supply/sanitation, and digital services. At the macro level, U.S.-based research indicates that the annual cost of power interruptions for the economy can reach tens of billions of dollars per year; the classic estimate by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) provides a reference point of approximately $79 billion/year (with a sensitivity range of $22–135 billion/year), while the majority of the damage falls on the commercial and industrial sectors.

4.1.1. Aggregate Macroeconomic Damage from Power Interruptions (USA)

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Estimate | ~$79 billion per year |

| Sensitivity range | ~$22 – 135 billion per year |

| Source | Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), Eto et al. |

| Document | “The Economic Impacts of Power Interruptions on Electricity Customers in the United States” |

| Link | The Economic Impacts of Power Interruptions on Electricity Customers in the United States |

| Methodology | Customer Damage Functions (CDF), aggregation by sectors |

| What it measures | Direct + indirect economic losses from interruptions |

| Sectors | ~72–73% commercial, ~26% industrial, <3% households |

| Limitations | USA; data should be extrapolated cautiously |

| Correct use | National scale, order of magnitude, not an “exact number” |

Hospitals and clinics (healthcare)

In healthcare, power outages are not only a financial issue but also a risk to patients, as a significant share of clinical processes is electricity-dependent: ventilators, dialysis, infusion pumps, monitoring, laboratory diagnostics, as well as IT layers (EHR/EMR, PACS, communications, medication management).

The financial aspect within a scientific framing is correctly described as follows:

- the cost of an incident is determined by (i) duration, (ii) how quickly and reliably the emergency power layer performed (generators/UPS), (iii) the scale of procedure disruption, (iv) damage to equipment/IT, and (v) secondary costs (patient transfers, logistics, staff overtime);

- there is no universal “single number for all hospitals” in the literature: it is correct to provide orders of magnitude and a linkage to methodology.

The engineering and regulatory dimension: requirements for emergency power in healthcare facilities (as an element of resilience) are formulated in specialized guidance for health facilities, where the focus is not on “nice numbers” but on ensuring continuity of critical functions.

Key conclusion: in healthcare, the “cost of an outage” is a function not only of economics but also of acceptable clinical risk; therefore, resilience here is always calculated as minimizing the probability of failure of critical loads, rather than as optimizing the “average bill.”

4.1.2.1 Financial Damage to Hospitals

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Typical damage per incident | ~$690,000 |

| Source | Ponemon Institute (cited by Eaton) |

| Document | Eaton Healthcare Power Reliability Report |

| Link | Eaton Healthcare Power Reliability Report |

| Methodology | Surveys + case analysis of IT and clinical disruptions |

| What is included | Procedure cancellations, evacuation, IT failures |

| What is not included | Cost of human life |

| Limitations | Average value; not universal |

| Correct use | Order of magnitude for large hospitals |

4.1.2.2 Cost of IT Downtime in Healthcare

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Cost of IT downtime | $7,500 – 25,000 / minute |

| Cost per hour (indicative) | ~$1.7 million (average), up to ~$3.2 million (large clinics) |

| Source | Eaton / Ponemon |

| Data type | IT downtime cost |

| Limitations | Depends on scale and degree of digitalization |

| Correct use | Emphasize non-linearity of damage |

Water supply and sanitation (water & sanitation)

Water supply and sanitation systems are structurally electricity-dependent: pumping stations, water treatment, sewage pumping, chemical dosing, and water quality monitoring. During power outages, the following may occur:

- pressure drops and disruptions of water supply,

- breakdown of technological processes (filtration/disinfection),

- increased sanitary and epidemiological risks,

- cascading impacts across urban services (hospitals, food supply chains, fire safety).

Quantitative anchor: for the City of Tshwane (South Africa), a published analysis shows that measures to ensure continuity of water supply against the backdrop of power interruptions yield a significant economic benefit, expressed as a benefit/cost ratio of approximately ~15 (in that case — based on annual calculations of benefits and additional costs).

4.1.3.1 Economics of Water Supply Resilience (Tshwane case)

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Population | ~3.1 million |

| Annual benefit | 170.46 million ZAR |

| Annual costs | ~11 million ZAR |

| Benefit/Cost | ≈ 15.5 |

| Source | South African Journal of Industrial Engineering |

| Link | South African Journal of Industrial Engineering — Cost–Benefit Analysis (Tshwane case) |

| Methodology | Cost–Benefit Analysis |

| Correct use | Illustration of the resilience multiplier |

4.1.3.2 Full Water Outage: Per-Capita Damage

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Damage | ~$97 per person per day |

| Source | FEMA (cited in academic works) |

| Context | Full water supply outage |

| Price year | ~2011 |

| Correct use | Scaling to a city/region |

Digital infrastructure and data (data centers / cloud / telecom)

For the digital economy, power outages at the facility level quickly translate into:

- direct revenue loss,

- SLA penalties,

- cascading service failures (B2B/B2C),

- reputational damage.

Quantitative anchor (Ponemon Institute research):

- in materials from trade press that summarize Ponemon’s findings on data centers, a reference point of average damage of approximately ~$505k per incident is cited (in the context of unplanned downtime);

- other reviews along the same line discuss broader ranges of the cost per incident (depending on organization type, redundancy architecture, and scenario).

4.1.4.1 Cost of a Data Center Downtime Incident

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Average damage per incident | ~$505,000 |

| Range | ~$38,969 – $1,017,746 |

| Source | Ponemon Institute (cited by Vertiv, InformationWeek) |

| Link | Data Center Outages Generate Big Losses |

| Methodology | Survey of data center operators |

| Correct use | Describe tail risk, not the average |

4.1.4.2 Cost per Minute of Downtime

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Average | > $5,000 / minute |

| Maximum | > $11,000 / minute |

| Source | Ponemon |

| Applicability | Enterprise / cloud / telecom |

Key conclusion: the cost of downtime in digital infrastructure is not a constant; it follows a “heavy-tail” distribution (tail risk), where rare major incidents account for a disproportionately large share of total damage.

4.2. Indirect Effects: Economy and Societal Stability

Industry and logistics

Industry and logistics are particularly sensitive to power interruptions due to:

- continuous technological processes,

- high costs of work-in-progress,

- risks of equipment damage during emergency shutdown/restart,

- cascading impacts across supply chains.

At the macro level, LBNL estimates indicate that a substantial share of total damage from power interruptions falls precisely on the commercial and industrial segments of the economy.

4.2.1 Downtime Cost in Industry (per hour)

| Source | Estimate |

|---|---|

| LBNL (CDF) | $69,284 / h (large C&I), $5,195 / h (small C&I) |

| Fluke (2025) | ~$1.7 million / h (average), up to $42.6 million / incident |

| ABB | $10,000 – 500,000 / h (7% — higher) |

| Link (Fluke) | Unplanned Downtime Costs Manufacturers Up to $852M Weekly |

| Link (ABB) | ABB — Downtime Costs and Industrial Impact |

Correct formulation:

- the range of downtime costs at the enterprise level varies by orders of magnitude (depending on the industry, degree of automation, and the product’s “value per hour”);

- in high-automation manufacturing and critical logistics hubs, the damage from stoppages can reach levels where it becomes meaningful to treat resilience as a component of competitiveness and supply security, rather than only as “insurance.”

Households and small business

For households and SMEs, there are fewer aggregated universal figures because methodologies differ (WTP/COI, direct/indirect costs, valuation of time, health, food spoilage, income loss). However, the overall effect is well described as follows:

- at the household level, losses may appear moderate,

- at the district/city level, they quickly scale to tens of millions per day when a power outage coincides with degraded water supply/communications,

- for SMEs, the key factor is digital revenue and cold chains (retail/HoReCa).

4.2.2 Households

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Losses per event (water) | ~$93.96 |

| Source | ScienceDirect |

| WTP for electricity | 0.36 – 19.4% of daily GDP / hour |

| Source | World Bank |

| Link | World Bank — Willingness to Pay for Electricity and Outage Valuation |

4.2.3 Small Business

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Incident cost | $82,200 – 256,000 |

| Per-minute downtime | $137 – 427 / minute |

| Source | IDC (cited) |

| Link | The Cost of Downtime |

Social trust and institutional effects

Repeated failures of basic services (electricity, water, communications) have measurable institutional aftereffects: people and businesses begin to perceive infrastructure instability as a “risk norm,” which affects:

- trust in institutions,

- investment behavior,

- migration decisions,

- political dynamics.

4.2.4 Social Trust and Institutional Effects

| Indicator | Value |

|---|---|

| Decline in trust in institutions (USA) | ~22 pp since the 1970s |

| Source | Urban Institute |

| Link | Understanding the Crisis in Institutional Trust |

| Regional effect | Dozens of pp difference in perception of preparedness |

| Source | World Risk Poll / Lloyd’s Register |

Section 4 conclusion

- The economic damage from power interruptions in a developed economy can amount to tens of billions of dollars per year; for the United States, a frequently used reference point in the literature is $79 billion/year (sensitivity range $22–135 billion/year).

- Critical infrastructure (healthcare/water/digital systems) exhibits a non-linear damage function: a short disruption may be tolerable, but under certain conditions (failed reserve start, disruption of water supply, failure of digital layers) the damage increases stepwise.

- The digital economy demonstrates a high incident cost for downtime of data centers/services (public reviews citing Ponemon indicate an order of hundreds of thousands of dollars per event, with wide dispersion).

- The social layer: resilience is not only an engineering KPI, but also an infrastructure of trust; repeated failures alter the long-term behavior of households and business.

5. AN ARCHITECTURAL APPROACH TO RESILIENT ENERGY

5.1. Architectural Principles (Not a Specific Device)

At the architectural level, resilience is based on six fundamental principles:

Principle 1: Local generation

Generation as close as possible to consumers (building rooftops, industrial sites, local sources), which reduces losses and dependence on trunk transmission lines.

Principle 2: Autonomous power nodes with island mode

Each node (hospital, communications hub, district) is capable of temporarily operating autonomously from the main grid, preventing cascade propagation.

Important: resilient island mode most often requires grid-forming capability (voltage/frequency formation) at the node — via inverters and/or synchronous/firm sources.

Principle 3: Modularity and redundancy without a single point of failure

Multiple sources can be combined such that the failure of one element does not lead to system failure:

| Technology | Day | Night | Variable | Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solar | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | Daytime generation |

| Wind | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Variable generation |

| BESS | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | Balancing / transients |

| Firm/dispatchable | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | Anchor power / reserve |

| Diesel | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | Emergency, prolonged stress |

The meaning: not to “replace everything with one thing,” but to build an architecture in which the failure of one subsystem does not disable critical loads.

Principle 4: Decentralized control and local automation

Decisions on segmentation, balancing, and load prioritization are made at the node level with fast response, not only by a central dispatcher.

Practical implementation:

- Local decision-making algorithms

- Mesh / redundant communication channels

- Graceful degradation upon loss of the center

Principle 5: Limiting dependence on fuel and bottleneck resources

Reducing the role of diesel generation as a day-to-day source, using it only as backup; reducing dependence on external supplies of fuel and critical materials.

Principle 6: Integrating cybersecurity into design

Applying unified authentication, encryption, and monitoring standards for all elements, including distributed sources.

These principles can be implemented using different technology stacks; what matters is the architecture of interconnections and reserves, not a specific model of generator or storage device.

5.2. Illustrative Example: A Critical Hospital Microgrid

Consider a model example (not a normative design, but an illustrative scenario) in which a hospital supports critical loads through a local microgrid:

Components (illustrative; not a “default” design):

- Solar: 100 kW (daytime share of load)

- BESS: 200 kWh (night / transients, balancing)

- Firm source: 50 kW (24/7 anchor power, if required)

- Diesel backup: 200 kW (emergency, prolonged stress scenarios)

- Smart controller: island mode, protections, synchronization, EMS

Operating modes:

- Normal: grid + solar (optimization)

- Night: BESS + firm source (dispatchable / grid-forming, if required)

- Cloudiness: firm + BESS compensate

- Blackout: island mode, prioritization of critical loads

- Prolonged stress: diesel as the “last layer”

Resilience:

Such an architecture allows:

- In normal operation — minimizing the load on the trunk grid

- During short-term disturbances — using storage and a solid-state source

- During serious failures — switching to island mode and prioritizing critical loads

Availability of critical loads is determined by N+1/N+2 redundancy and correct operating-mode management.

6. TECHNOLOGY LANDSCAPE AND TRL LOGIC

6.1. TRL as the Language of Technology Maturity

The Technology Readiness Level (TRL) scale is used by energy agencies and research organizations to assess technology maturity:

- TRL 1–3: fundamental research and laboratory demonstrations of principles

- TRL 4–6: prototypes and systems tested in a relevant environment

- TRL 7–8: demonstration projects in a real operational environment

- TRL 9: commercially operated, widely deployed solutions

For critical-purpose infrastructure (hospitals, water utilities, transport), solutions at TRL 8–9 with demonstrated reliability and environmental profile are typically required.

6.2. Current Maturity of Technologies

Solar PV (TRL 9)

- Mature technology, widely deployed

- Variable generation requires combination with storage

- LCOE depends on geography and financing

Wind (Onshore) (TRL 9)

- Mature technology

- Variability requires grid flexibility

BESS (Li-ion) (TRL 9)

- Mature technology

- Constraints: degradation, temperature regimes, supply chains

- Replacement and recycling strategy

Traditional generators

- Diesel and gas generators — mature (TRL 9)

- Provide dispatchable capacity

- Constraints: emissions, fuel supply chains

- Their role is logically limited to backup functions

6.3. Solid-State Electrodynamic Systems (VENDOR.Max class)

Status: Emerging class of technologies at TRL 5–6

Architectural framing (publicly correct):

- A regime-based electrodynamic system with a stable operating regime

- Prototypes have demonstrated a stable operating regime in laboratory and limited field conditions

- Require further demonstrations and certification

Positioning within the architecture:

Architecturally, such systems can be viewed as scalable modules for a share of firm load (baseload) within microgrids, while key operational parameters (longevity, grid integration, environmental profile in an LCA sense) must undergo independent verification.

Important: this is not a “magical device” that by itself solves the resilience problem. It is a representative of a class of modular sources that can occupy a niche within microgrid architecture as weather-independent base power at the kilowatt scale.

6.4. TRL Trajectory 2026–2035 (Scenario Logic)

Near-term (2026–2027):

- Field pilots and independent engineering validation

- TRL 6→7 upon successful validation

- Certification pre-testing

Medium-term (2027–2029):

- Expanded pilots, certification

- First scalable deployments of microgrids

Long-term (2030+):

- Industrialization of modular DER architectures as a resilience standard

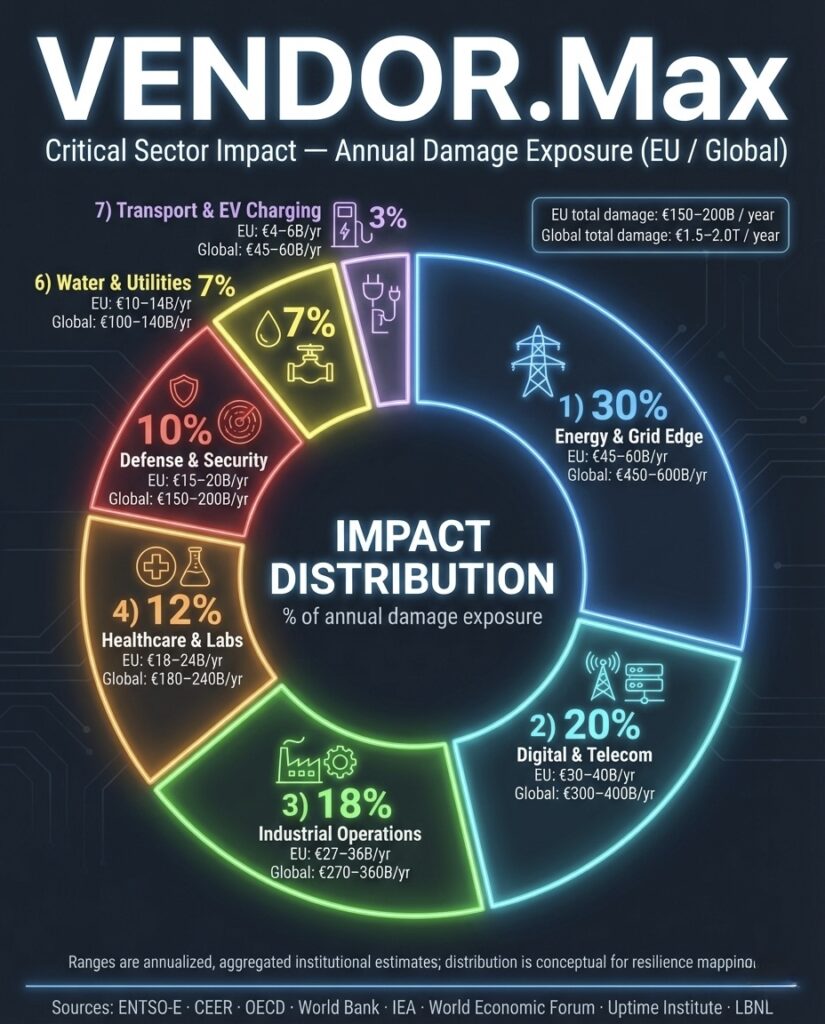

Figure 1. Sectoral distribution of annual economic damage exposure from power outages (EU / Global).

Aggregated, annualized institutional estimates based on public data from ENTSO-E, CEER, OECD, World Bank, IEA, World Economic Forum, Uptime Institute, and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Values represent order-of-magnitude exposure and are used here to illustrate resilience prioritization, not as precise forecasts or technology-specific claims.

7. SOLID-STATE SYSTEMS OF THE VENDOR.MAX CLASS

Role within a resilience architecture, engineering logic, and environmental profile Figure 1 represents an illustrative aggregated order-of-magnitude assessment, not a forecast of economic performance or investment returns.7.1. How the system works: regime, not an “energy source from nowhere”

VENDOR.Max is designed as an open electrodynamic system operating in a stable operating regime. The key idea here is not in “creating energy,” but in forming and maintaining a controlled regime, from which useful electrical power is then linearly extracted. The system architecture is divided into two functional contours:- Regime-formation contour — responsible for creating and stabilizing the working electrodynamic state.

- Linear power extraction contour — delivers useful electrical power via a separate, controlled path.

- Control and buffer layer — ensures regime stability under changes in load and conditions.

7.2. Modularity: 2.4 kW as a building block

The basic unit of VENDOR.Max is a 2.4 kW module. The system is designed from the outset to be modular and scalable. The operating principle is analogous to industrial modular UPS systems:- each module is autonomous and has its own protections,

- power is increased by adding modules,

- failure of one element does not stop the entire system.

- 10 modules × 2.4 kW = 24 kW of installed capacity,

- if one module fails, the system continues operating at reduced power.

7.3. Environmental profile: what is correct to state publicly

The system contains no fuel combustion processes. This means that:- under normal operating conditions, there are no local exhaust emissions characteristic of diesel and gas generators;

- there are no NOx, CO, and particulate emissions associated with combustion;

- continuous fuel logistics are not required.

- it uses semiconductors, copper, and structural materials;

- the equipment requires responsible handling at end-of-life;

- the full environmental profile is assessed via standard life-cycle methodologies (LCA) and is subject to independent validation.

- reduce local environmental impact,

- decrease dependence on fuel,

- and at the same time avoid loud or incorrect statements not supported by certification.

8. MODULAR ARCHITECTURE AND RESILIENCE TOPOLOGY

From Beyond BESS to a firm cell of the power system8.1. Beyond BESS: why architecture matters more than source type

As shown in the article Beyond BESS: TESSLA and VECSSES Solid-State Energy the key problem of modern microgrids lies not in the absence of generation as such, but in the absence of a resilient firm cell capable of:- operating for long durations, rather than minutes or hours;

- not depending on weather conditions;

- not requiring fuel logistics;

- maintaining operability under partial failures.

- supplement an existing system,

- or replace it entirely, forming an autonomous resilient cell.

8.2. Modularity as the basis of a firm cell

The basic unit of VENDOR.Max is a 2.4 kW module. The system is designed from the outset as a multi-level modular structure, not as a monolithic агрегат. Key architectural properties:- Parallel topology (parallel architecture) Each module operates autonomously, without rigid dependence on neighboring modules.

- Absence of a single point of failure Failure of one or several modules reduces available power, but does not result in loss of function.

- Structural redundancy (N+1 / N+2 / N+x) Redundancy is achieved not by duplicating the entire installation, but by the architecture itself.

- Graceful degradation The system degrades in power, not in operability.

8.3. The role of diesel: an extreme emergency layer, not a working element

It is important to fix a correct and strict position. A diesel generator is not a mandatory element of the architecture if:- VENDOR.Max firm capacity is sufficient to cover critical loads;

- the architecture is modular and redundant;

- load redistribution is implemented.

- exclusively the “everything else failed” scenario;

- does not participate in normal or stress operation;

- is not part of the resilient regime.

8.4. Operating modes: VENDOR.Max as an active participant, not a “night crutch”

VENDOR.Max participates in all modes, not only “night” or emergency modes. Normal mode (grid available)- Grid + Solar + VENDOR.Max

- BESS is used for smoothing and optimization, not as the primary source.

- VENDOR.Max as the base firm layer

- BESS — for peaks and transients.

- VENDOR.Max maintains the regime and critical loads;

- BESS smooths dynamics;

- Renewables connect when available.

- VENDOR.Max continues operating without time-based degradation;

- diesel is not required if the architecture is designed correctly.

- supplement the grid,

- replace the grid,

- become the core of an autonomous power system.

8.5. Distributed topology: homes, transport, public facilities

In line with the logic of the Beyond BESS article, resilience architecture should be considered not at the level of a single facility, but as a distributed network of cells. The key mechanism is dynamic redistribution of energy between nodes:- residential homes;

- electric vehicles (V2H / V2G / V2X);

- public buildings (schools, kindergartens);

- critical facilities (hospitals, pumping stations, communications).

- as a local firm cell of a home or building;

- as an anchor node of a neighborhood;

- as an anchor source for critical loads around which energy is redistributed from other nodes.

8.6. Final position

VENDOR.Max can be considered as:- an element of a hybrid microgrid,

- a universal backup power node,

- or, with appropriate design and scaling, capable of partially replacing traditional generation and backup architectures in certain application scenarios.

9. THE ECONOMICS OF ENERGY RESILIENCE: A SCENARIO MODEL

9.1. Analytical Framework and Assumptions

The economic calculations presented below are a scenario-based illustrative model intended to analyse the logic of the relationship between the cost of power supply failures and investments into an energy-resilience architecture. They are not a forecast of returns, do not constitute an investment recommendation, and do not substitute for a full financial analysis of a specific facility. All values provided are conditional, rounded, and sensitive to the following key parameters:- the price of electricity purchased from the centralized grid;

- capital expenditures (CAPEX) for solar generation, energy storage, and modular resilient sources;

- the actual frequency, duration, and nature of power outages;

- cost of capital (discount rate, weighted average cost of capital);

- the required reliability level for critical loads (Service Level Agreement);

- the facility load structure, in particular the share of consumption attributable to critical functions.

9.2. Case: Hospital — Three Scenarios

A hypothetical hospital is considered with an average annual electricity bill of approximately €500,000, typical for a large urban medical facility. Conservative scenario (absence of a microgrid; assessment of failure risk only) Based on sector reviews and retrospective analyses, it is assumed that major power outages that materially affect the hospital’s operation occur approximately once every 20 years, corresponding to an annual probability: p = \frac{1}{20} = 5\% The estimate of direct economic losses from one such incident (cancellation of surgeries, downtime of diagnostic equipment, damage to sensitive systems, organization of temporary solutions) is taken at €600,000 per event, corresponding to the order of magnitude documented in sector studies for healthcare facilities (Ponemon Institute; Eaton Healthcare Report). The expected annual damage (risk cost) is calculated as: E[damage] = p \times loss = 0{,}05 \times 600\,000 \approx 30\,000 \text{ euro per year} Thus, when analysed in expected-value terms, the implied budget burden for the hospital is:- approximately €500,000 per year — guaranteed electricity expenditure;

- approximately €30,000 per year — the expected value of rare but costly emergency events.

- solar generation;

- an energy storage system;

- a modular resilient power source (solid-state or another weather-independent class);

- an intelligent control system with island-mode support.

- capital expenditures for equipment and installation: €600,000–800,000;

- reduction in annual electricity expenditures through self-generation and load optimization: €150,000–200,000 per year;

- reduction of expected damage from major outages to €5,000–10,000 per year, instead of the previous ~€30,000 per year.

- direct cash flow from reduced electricity costs; and

- the effect of reducing the expected value of outage-related damage,

- with CAPEX of €600,000 and an effect of €225,000 per year — about 2.7 years;

- with CAPEX of €800,000 and an effect of €170,000 per year — about 4.7 years.

- operating expenditures for microgrid maintenance (e.g., 1–2% of CAPEX, i.e., €6,000–16,000 per year);

- more conservative estimates of electricity savings;

- the frequency of serious outages increases to one event every 5–10 years (annual probability 10–20%);

- expected damage without a microgrid increases to €60,000–120,000 per year;

- electricity tariffs increase, raising the hospital’s annual bill to €600,000–700,000;

- capital expenditures may increase due to equipment inflation and project complexity.

- avoided losses from outages (the difference in risk cost before and after microgrid deployment) may rise to €40,000–80,000 per year;

- absolute electricity savings increase due to higher tariffs.

- the actual risk and nature of outages;

- the structure and criticality of loads;

- tariff policy and price outlook;

- cost of capital and availability of subsidies;

- regulatory requirements for reliability.

9.3. Grid-Level Economics

Historical major blackouts demonstrate that a single cascading failure in a centralized system can lead to losses ranging from hundreds of millions to several billions of euros or dollars:- Italy, 2003 — approximately €1.18 billion in total damage (Schmidthaler & Reichl, CIRED);

- Northeastern United States and Canada, 2003 — $7–10 billion (ICF Consulting for the U.S. Department of Energy).

- critical facilities can transition to island mode and minimize downtime;

- the system acquires multi-level segmentation;

- the probability of a “one cascade — half a continent” scenario statistically decreases.

9.4. Sensitivity of the Economic Model to Key Parameters

Even in a simplified scenario model, the economics of energy resilience demonstrate high sensitivity to a number of input parameters. This confirms the necessity of abandoning “a single payback number” in favor of ranges and scenarios. Resilience economics: comparison of two architectures Scenario A — microgrid WITHOUT a firm layer (Solar + BESS + Diesel) Scenario B — microgrid WITH a firm layer (VENDOR.Max) (Solar + BESS + VENDOR.Max + Diesel as an extreme reserve) Table. Direct comparison| Criterion | Without firm layer | With firm layer (VENDOR.Max) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline logic | All autonomy via BESS | Autonomy via regime + BESS |

| Autonomy duration without fuel | 1–6 hours (practically) | 24/7 (firm layer) |

| Required BESS capacity | High (hours/days) | Lower by 30–60% |

| CAPEX on BESS | High | Lower |

| Diesel usage | Often during prolonged failures | Almost never |

| Fuel dependence | High | Minimal |

| Sensitivity to diesel price increases | Critical | Almost absent |

| Tail risk (catastrophic scenario) | Persists | Significantly reduced (but not eliminated) |

| Failure risk under a multi-day blackout | High | Substantially lower with correct architecture |

| Guaranteed operation of critical loads | Conditional | Effective |

| Economics under rare failures | Acceptable | Acceptable |

| Economics under frequent failures | Breaks down | Improves |

| Architectural resilience | Limited | Systemic |

9.5. The Economic Role of VENDOR.Max in the Beyond BESS Architecture

9.5.1. Limitations of the Classic “Solar + BESS + Diesel” Model

In the classic microgrid architecture, resilience economics is built around three elements:- solar generation as a source of low-cost but variable energy;

- BESS as an instrument for smoothing and short-term autonomy;

- a diesel generator as an emergency backup.

- BESS does not scale linearly by autonomy duration Increasing autonomy from 4 to 24 hours implies a multiple increase in CAPEX and accelerated battery degradation (NREL, LBNL).

- A diesel generator creates hidden costs

Even with rare use, it requires:

- regular testing,

- fuel logistics,

- reserves for emergency starts,

- accounting for emissions and regulatory constraints.

- Tail-risk economics remains

In scenarios of:

- a multi-day blackout,

- disruption of fuel supply chains,

- failure of the diesel generator start sequence,

9.5.2. TESSLA & VECSESS Topology: the Place of VENDOR.Max

In the architecture described in the article “Beyond BESS: TESSLA and VECSSES Solid-State Energy”, VENDOR.Max is introduced not as a replacement for a single element, but as a structural firm layer located: between energy storage systems and emergency diesel generators, or, in a number of scenarios, as the only resilient power node with multi-level redundancy. From a topology perspective:- BESS handles fast transients and millisecond response;

- VENDOR.Max provides long-duration weather-independent base power without fuel;

- the diesel generator is pushed into an extreme emergency contour used statistically rarely.

9.5.3. Direct Economic Value of VENDOR.Max

The economic effect of including VENDOR.Max manifests not in a single budget line, but across multiple dimensions: 1. Reduction of required BESS volume The presence of a firm layer allows:- reducing the battery capacity required for a given autonomy level;

- reducing CAPEX on BESS;

- slowing battery degradation through lower depth-of-cycle usage.

- eliminates the risk of fuel unavailability;

- eliminates the risk of diesel generator non-start;

- reduces the probability of evacuations, cancelled operations, and systemic failures.

- is rarely incorporated in simple models,

- but dominates in real catastrophic scenarios (LBNL, DOE).

- there are no ongoing fuel expenses;

- environmental compliance burden is reduced;

- meeting emissions and noise requirements is simplified.

- residential homes,

- electric vehicles,

- schools, kindergartens,

- hospitals and municipal facilities

- reduces load on the trunk grid;

- reduces total damage during blackouts;

- shifts part of losses from the “systemic” category to “locally manageable.”

9.5.4. Summary on the Economics of VENDOR.Max

From an economic perspective, VENDOR.Max:- can serve as an additional firm layer that increases architectural resilience;

- can be considered as the primary resilient power node for autonomous or critical facilities;

- does not compete directly with solar generation or BESS, but changes the shape of the entire economic model, reducing both CAPEX extremes and the risk of rare but destructive events.

10. POLICY AND REGULATION: RESILIENCE AS A NEW STANDARD

10.1. The European Track: the Critical Entities Resilience Directive (CER) and the European Grids Package

Critical Entities Resilience Directive (CER) Factual regulatory framework (based on official European Union sources) Directive (EU) 2022/2557 on the resilience of critical entities (Critical Entities Resilience Directive, CER) entered into force in January 2023 and replaced the previously applicable directive on European critical infrastructure. In accordance with the Directive:- by 17 October 2024, the Member States of the European Union were required to adopt and publish national measures transposing the CER and to notify the European Commission thereof;

- these measures must apply from 18 October 2024, i.e., from that date the Directive effectively entered practical application at Member State level;

- by 17 January 2026, each Member State is required to:

- prepare a national strategy to enhance the resilience of critical entities;

- conduct a national risk assessment for the sectors falling under the scope of the Directive.

- regularly conduct risk assessments, including risks of failures, cascading events, climatic impacts, and deliberate attacks;

- develop and maintain resilience plans covering technical, organizational, and physical measures;

- ensure the capability to prevent, protect against, respond to, resist, mitigate, absorb, adapt to, and recover from incidents.

- elimination or reduction of dependence on single points of failure (single point of failure);

- increasing the autonomy of critical facilities;

- the capability to continue functioning in the event of partial or full unavailability of the transmission grid.

- providing a stable base load without dependence on fuel logistics;

- complementing energy storage, reducing capacity requirements;

- reducing dependence on emergency diesel generators, which remain a last-resort backup rather than the basis of resilience.

- the European Commission Communication on the European Grids Package (COM(2025) 1005);

- proposals to adjust and expand the application of the TEN-E Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2022/869);

- amendments to the renewables directives and electricity market design to accelerate permitting procedures;

- Grid Connection Guidance on grid access and queue management;

- guidance on Contracts for Difference and a comprehensive Impact Assessment.

- accelerating permitting procedures for renewables projects, energy storage, and hybrid “renewables plus storage” systems;

- transitioning to the first-ready, first-served principle, under which priority is given to projects that are technically and organizationally ready for connection and have grid characteristics that improve system resilience and controllability;

- implementing the resilience-by-design principle, including integration of physical and cybersecurity, consideration of climate risks, and reliability requirements at the design stage;

- explicit inclusion of resilience-enhancement measures in the list of projects financed through the Connecting Europe Facility.

- more distributed and segmented;

- more flexible and digitally controllable;

- capable of effectively integrating distributed generation, storage, and microgrids;

- designed with fault tolerance and automatic restoration in mind.

10.2. The United States of America: Regulatory Response and Resilience Programs

In the United States, the key driver of investments into energy-system resilience has been the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law of 2021. Under this law:- approximately $65 billion was allocated to grid modernization and resilience enhancement;

- of which $10.5 billion was allocated to the Grid Resilience and Innovation Partnerships (GRIP) program administered by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Grid Deployment Office.

- nearly $3.5 billion was awarded to 58 projects in 44 states;

- the total investment volume including cost-share amounted to approximately $8 billion.

- hardening and modernization of grid infrastructure, including undergrounding lines in vulnerable regions;

- deployment of smart grids, energy storage, distributed generation, and microgrids;

- creation and expansion of so-called resilience hubs — facilities combining solar generation, storage, and local networks to provide critical services to communities during natural disasters and large-scale outages.

10.3. Global Infrastructure Development Initiatives

International financial institutions, primarily the World Bank and regional development banks, have in recent years significantly increased financing of projects related to:- modernization of transmission and distribution networks;

- deployment of decentralized and renewable energy, including mini-grids and autonomous systems;

- integration of climate adaptation and energy access into a unified investment framework.

- centralized grids continue to develop and modernize;

- decentralized solutions such as mini-grids and autonomous systems are used to enhance resilience and coverage;

- resilience and climate adaptation are treated as key criteria of investment viability rather than as secondary environmental factors.

11. WHY THIS IS A NECESSITY OF THE PRESENT, NOT OF THE FUTURE

11.1. Energy Resilience as a Layer of Civil Protection

The combination of three factors — aging energy infrastructure, increasing frequency of extreme weather events, and intensifying geopolitical risks — shifts power-system reliability from the category of operational efficiency into the category of civil protection and systemic societal resilience. Major blackouts of the last two decades (Italy 2003, India 2012, Northeastern US and Canada 2003, regional outages in Europe and North America in the 2010s and 2020s) demonstrate a stable pattern: a power supply failure lasting hours rapidly translates into disruptions of healthcare, water supply, transport, communications, and digital services, leading to measurable economic losses and social consequences. According to Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the U.S. Department of Energy, total annual damage from power interruptions in the U.S. economy is estimated in the range of $22–135 billion per year, with the most likely estimate around $79–80 billion, and more than 95% of losses falling on the commercial and industrial sector. Similar ratios are observed in other developed economies. Against this backdrop, microgrids, local generation sources, modular generators, and energy storage integrated directly into the architecture of critical infrastructure (hospitals, water utilities, data centers, communications hubs) de facto move from the category of “optional improvements” into instruments for meeting resilience requirements and reducing systemic risks. This is particularly characteristic for jurisdictions where regulatory frameworks such as the Critical Entities Resilience Directive and the European Grids Package are already in force.11.2. Three Pressures Shaping the “Now”

Pressure 1: Infrastructure age In a number of developed countries, a significant share of grid assets — transmission lines, transformers, substations — has been in operation for 40–60 years or more, exceeding the originally designed service life. Analyses for the United States and Europe indicate that without accelerated modernization and grid segmentation, failure frequency and the risk of major emergency events over a 10–20-year horizon will increase, even if current consumption levels are maintained. Pressure 2: Climate and extreme weather Data from meteorological and climate agencies show a persistent increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme events — storms, heat waves, floods, and wildfires. These events impose concentrated stress on lines and substations, turning individual nodes into points of fragility. Combined with the growing share of variable renewable sources without adequate compensating measures, this complicates grid control and increases the likelihood of conditions under which a local event can trigger a cascading failure. Pressure 3: Political will and compliance At the European Union level, the CER Directive and the European Grids Package initiatives establish resilience as a mandatory requirement for critical entities and new infrastructure. In the United States, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and U.S. Department of Energy programs (including GRIP) direct tens of billions of U.S. dollars toward enhancing grid resilience, expanding storage, distributed generation, and microgrids. Taken together, this creates a new regulatory and institutional standard: infrastructure operators are expected not to merely declare redundancy, but to demonstrate provable architectural resilience.11.3. Architecture Matters More Than an Individual Device

In the context of VENDOR.Max-class solutions, it is fundamentally important to fix the correct engineering and regulatory optics. The point is not an “universal self-sufficient device” that solves the resilience task on its own, but a self-sufficient load power source that is integrated as a building block within a resilience architecture. Resilience is formed not by an individual device, but by the configuration of sources, storage, redundancy, and control. The factual value of such solutions is determined not by their existence as standalone products, but by:- how they are integrated with renewables, energy storage, traditional backup generation, and control systems;

- what resilience topology they form at the level of a facility, cluster, or microgrid;

- completion of the full cycle of technology maturity, independent validation, and certification.

12. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

12.1. Final Position

The global power grid system is at a point of structural inflection, where issues of reliability and resilience move beyond operational efficiency and become factors of economic, social, and institutional stability.- United States: the combination of aging grid assets, growing demand (including the digital economy and electrification), and limited reserve of dispatchable (firm) capacity increases the risk of both local and systemic failures. This is reflected in the assessments of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), which record an increase in the frequency and aggregate cost of power interruptions (Aging Electric Infrastructure in the United States).

- Europe: incidents in recent years, including the 28 April 2025 blackout on the Iberian Peninsula, have shown that the development of cascading events and the loss of tens of gigawatts of load can occur within seconds to tens of seconds under certain combinations of disturbances, protection characteristics, and limited grid segmentation. This underscores the vulnerability of centralized architectures under complex dynamic operating conditions (Blackouts Aren’t New, But Is Europe’s Grid Ready for the Next One?).

- Globally: electrification deficits, high outage frequency, and weak infrastructure resilience in a number of regions make architectural resilience not an additional option but a baseline infrastructure necessity for public health, economic functioning, and trust in institutions (Global Electricity Access Stalls as Africa’s Progress Slows).

12.2. Architectural Choice

Under the described risks, two fundamentally different development trajectories are forming. Path A — preservation of an architecture of fragility (purely centralized model):- high probability of major economic losses in stress events, reaching from hundreds of millions to billions of dollars or euros per blackout (Power Interruptions: A Costly Problem for the U.S. Economy);

- growth of social costs, including risks to healthcare, declining trust in institutions, migration and investment effects (Infrastructure Disruptions: How Instability Breeds Household Vulnerability);

- intensification of climate, cyber-physical, and geopolitical threats to critical infrastructure.

- investments in local sources, storage, modular firm layers, and control systems are comparable in scale to the aggregate cost of several major crisis events, while delivering a long-term effect of reducing systemic risks (Understanding the Cost of Power Interruptions to U.S. Electricity Customers);

- the resilience of critical services — healthcare, water supply, digital infrastructure — increases by reducing the depth and duration of failures (Resilience of the Energy System: Impacts of Disruptions on Society);

- an infrastructure of trust is formed: the ability to demonstrate to society, business, and investors that key services are protected even under external shocks (Poor Infrastructure Resilience Damaging Public Confidence in Disaster Preparedness).

12.3. Recommendations

For infrastructure operators- Microgrids for high-risk facilities: begin planning and phased deployment of microgrids for hospitals, water utilities, data centers, and communications hubs over the 2026–2027 horizon, taking into account local risks and regulatory requirements (Framework for Decentralized Energy Resilience Islands).

- Pilots of new-class firm solutions: consider solid-state and modular sources as pre-commercial firm modules within controlled TRL 5→7 pilots, with mandatory independent validation, certification, and limited application until reaching TRL 8–9 (NETL Program Overview: Definitions).

- Architectural approach instead of waiting for an “ideal device”: already now deploy combinations of distributed generation, storage, backup sources, and advanced EMS, reducing risk through system structure rather than through a single technological element (EFCA 2025 Future Trends Report: The Resilience of the European Energy System).

- Island mode as a functional requirement: treat the capability for safe and controllable autonomous operation as a mandatory characteristic of critical facilities, especially in regions with high blackout risk and extreme weather events (Microgrids for the 21st Century: The Case for a Defense Energy Architecture).

- fund the TRL 5–8 transition for new firm classes through grants, pilot programs, and joint projects with infrastructure operators, tying support to transparent roadmaps and independent testing (PNNL Technical Report (PNNL-21737));

- harmonize certification requirements for microgrids, distributed generation, and new sources across interconnection, safety, cyber-resilience, and environmental profile dimensions (Critical Infrastructure and Cybersecurity);

- incentivize resilience investments through financial and tariff mechanisms that account for avoided blackout damage, not only current electricity cost (World Bank: Infrastructure Overview);

- synchronize compliance timelines and requirements (including the CER Directive) with engineering feasibility and technology availability (Critical entities resilience directive enters application to ensure protection of critical infrastructure).

- account for the deep-tech timeline: for VENDOR.Max-class solutions and analogous modular firm sources, it is realistic to expect 2–3 years to reach TRL 7, subject to successful completion of engineering milestones, independent testing, and absence of regulatory blockers (Technology Readiness Level);

- think in terms of an architectural stack rather than a single product: microgrids, storage, firm modules, and EMS form a unified resilience market with risk distribution across layers (Energy resilience and system architecture (ScienceDirect));

- finance field validation TRL 6→7 as the key de-risking stage, supporting demonstration projects with independent measurements and publication of results (New Infrastructure Act Funding Releases $3.5B Toward Grid Resilience, Microgrids Nationwide);

- require an evidence ladder: measurement protocols, independent test results, auditable models, and LCA assessments before transitioning from pilots to scaling (Nature Communications: Evidence and validation (Article)).

12.4. Time for Action

Infrastructure operators and jurisdictions that begin systematic deployment of microgrids and resilience architectures in 2026–2027 will, with high probability, obtain:- a competitive advantage, where reliability becomes a factor in location choice for businesses and populations;

- timely compliance with new regulatory frameworks (CER in the EU, DOE programs, and analogous initiatives in other regions);

- better preparedness for climate, geopolitical, and demand shocks;

- participation in shaping standards and best practices for the next generation of infrastructure projects.

FAQ

- Why are centralized power systems vulnerable to blackouts?Centralized power systems are vulnerable due to their architecture: large generators, long transmission lines, and unified control centers create conditions under which a single failure or error can grow into a cascading systemic disruption.This is why worldwide the transition from monolithic grids to architectures with decentralized nodes and autonomous microgrids is increasingly analysed.

- What is an energy resilience architecture (resilience)?An energy resilience architecture is a systemic approach to designing power supply in which failure of individual components does not lead to loss of critical functions.It includes local generation, autonomous nodes with island mode, modularity, absence of a single point of failure, and decentralized control — i.e., it is effectively based on the principles of decentralized power supply.

- Will microgrids replace traditional transmission grids?No. Microgrids do not replace transmission grids; they complement them.A decentralized architecture reduces the load on transmission infrastructure, increases resilience, and provides redundancy, while transmission grids remain critical for interregional energy exchange.

- Is it possible to rely entirely only on solar and wind energy?A high share of variable renewables without additional elements complicates frequency and grid stability management.Therefore, resilient power-supply architectures use a combined approach: renewables, storage, dispatchable (firm) sources, and local control within decentralized microgrids.

- Are batteries needed if solid-state energy sources are used?In most decentralized architectures, storage remains an important element for fast response and smoothing of transient regimes.Solid-state sources perform a different function — stable base power — and are used together with storage, not instead of it.

- What does TRL 5–6 maturity mean for VENDOR.Max-class technologies?TRL 5–6 means that the technology has been demonstrated at prototype level in a laboratory or relevant environment, but still requires large-scale pilot deployments and certification.Such technologies typically pass to the next stage of development within decentralized microgrids and infrastructure pilots.

- Do “zero emissions” mean no environmental impact?In normal operation, the absence of combustion processes means the absence of local exhaust gases.However, a correct assessment of the sustainability of any decentralized energy system requires full life-cycle analysis (LCA) and independent validation.

- Is microgrid economics guaranteed?The economics of decentralized microgrids are always context-dependent.Payback depends on electricity cost, CAPEX, outage frequency, regulatory requirements, and cost of capital; therefore it is correct to speak of scenario models rather than fixed return timelines.

REFERENCES / VERIFIED SOURCES

1. Grid reliability, macroeconomic impacts, and systemic risk

-

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL).

The Economic Impacts of Power Interruptions on U.S. Electricity Customers.

U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Analysis & Environmental Impacts Division.

The Economic Impacts of Power Interruptions on U.S. Electricity Customers

-

U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

Evaluating U.S. Grid Reliability and Security. July 7, 2025.

-

North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC).

Long-Term Reliability Assessment (LTRA) 2024.

-

ICF Consulting.

The Economic Cost of the August 2003 Blackout in the Northeastern United States.

Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy.

-

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL).

Understanding the Cost of Power Interruptions to U.S. Electricity Consumers.

Understanding the Cost of Power Interruptions to U.S. Electricity Consumers

2. Historical blackouts and systemic incidents

-

ENTSO-E.

System Separation Event on 28 April 2025 — Iberian Peninsula.

System Separation Event on 28 April 2025 — Iberian Peninsula

-

Reuters.

Spain and Portugal hit by major power outage. April 28, 2025.

-

Schmidthaler, M., Reichl, J.

Blackout Cost Estimation Methodologies and Applications. 2016.

(Referenced in blackout-simulator.com)

3. Healthcare systems and critical medical infrastructure

-

World Health Organization (WHO).

Emergency Power Supply Systems for Health Facilities. 2023.

-

Ponemon Institute.

Cost of Data Center Outages. (Healthcare-related sections).

-

Eaton.

Blackout Tracker: Healthcare Sector Impacts.

-

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

The Impact of Infrastructure Disruptions on Health Systems.

4. Water supply, sanitation, and urban infrastructure

-

World Bank.

The Cost of Service Interruptions in Urban Water Supply.

-

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Resilience in the Water Sector.

-

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Benefit-Cost Analysis for Water System Resilience.

(per-capita damage estimates).

-

SciELO South Africa.

Cost–Benefit Analysis of Water Supply Resilience in Tshwane.

5. Data centers, telecommunications, and digital economy

-

Uptime Institute.

Annual Outage Analysis.

-

Vertiv.

Cost of Data Center Outages. (Industry synthesis).

-

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL).

Resilience Valuation and Grid Outage Impacts.

6. Industry, logistics, and supply chains

-

Allianz Global Corporate & Specialty (AGCS).

Business Interruption Risk Report.

-

ABB.

Industrial Downtime Costs — Survey Results.

Industrial downtime costs up to $500,000 per hour and can happen every week

-

Fluke.

Unplanned Downtime Costs for Manufacturers. 2025.

-

McKinsey & Company.

The Cost of Supply Chain Disruptions.

7. Households, SMEs, and population vulnerability

-

World Bank.

Infrastructure Disruptions: How Instability Breeds Household Vulnerability.

Infrastructure Disruptions: How Instability Breeds Household Vulnerability

-

American Economic Association (AEA).

Conference papers on income loss during electricity disruptions.

Conference papers on income loss during electricity disruptions

-

Bloom Energy.

A Day Without Power: Outage Costs for Businesses.

8. Institutional trust, social effects, and crisis governance

-

Urban Institute.

Understanding the Crisis in Institutional Trust. 2024.

-

Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

World Risk Poll: Infrastructure Resilience & Trust.

Poor infrastructure resilience damaging public confidence in disaster preparedness

-

Internet Society.

Policy Briefs on Infrastructure Disruptions and Trust.

-

National Institutes of Health (NIH) / PubMed Central.

Political Trust and Crisis Management.

9. Regulation, policy frameworks, and infrastructure governance

-

European Commission.

Critical Entities Resilience (CER) Directive.

-

European Commission — Energy.

European Grids Package (COM/2025/1005).

-

European Commission.

Critical Infrastructure and Cybersecurity.

-

U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

Grid Resilience and Innovation Partnerships (GRIP).

-

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL).

Technology Readiness Levels and Energy System Innovation.

-

World Bank.

Infrastructure, Resilience, and Climate Adaptation.

10. Microgrids, architecture, and resilience-by-design

-

Stanford / Energy Institute & SEI.

Framework for Decentralized Energy and Resilience Islands.

-

National Defense University Press.

Microgrids for the 21st Century: The Case for a Defense Energy Architecture.

Microgrids for the 21st Century: The Case for a Defense Energy Architecture

-

UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC).

Resilience of the Energy System: Impacts of Disruptions on Society.

Resilience of the Energy System: Impacts of Disruptions on Society

-

Microgrid Knowledge.

Infrastructure Act Funding and Grid Resilience Projects.

New Infrastructure Act Funding Release $3.5B Toward Grid Resilience, Microgrids Nationwide

11. Technology readiness, validation, and evidence standards

-

Sciencedirect / Elsevier.

Technology Readiness Levels (TRL): Definition and Application.

Technology Readiness Levels (TRL): Definition and Application

-

Nature Communications.

Evidence, Validation, and Risk in Emerging Energy Technologies.

Evidence, Validation, and Risk in Emerging Energy Technologies

12. Vendor.Energy — architectural reference

-

Beyond BESS: TESSLA and VECSSES Solid-State Energy.