Champions of Innovation. Davos 2026. USA House. Hewlett Packard Enterprise and VENDOR.Energy

Decentralized Energy Infrastructure: Architecture, Security, and Sovereignty in the Davos 2026 Agenda

The story of this participation began late Tuesday night, January 21, 2026 (Davos time), with the receipt of a VIP invitation from Hewlett Packard Enterprise to attend the closed-door Champions of Innovation event hosted within the USA House.

The invitation was sent to a corporate technical email address that had not been used in any public forum registrations and did not appear in open participant lists.

It later became clear that this invitation was preceded by an independent review of the project by HPE, including an assessment of publicly available materials, digital traces, and the overall architectural logic of the solution. In the Davos context, such signals typically reflect interest not in presentation format or narrative, but in structural soundness—specifically, in how a project addresses real systemic constraints across energy, networks, governance, security, and infrastructure resilience.

What Scott Bessent Emphasized: Growth, Infrastructure, and the Limits of the Current Model

On the margins of Davos, a framework was clearly articulated—one that is increasingly becoming the starting point for economic planning. Across public statements and closed-door discussions, a broad consensus emerged: sustainable growth is impossible without innovation, and innovation can no longer exist independently of infrastructure.

In this context, innovation is not framed as a byproduct of “startup culture,” nor as a series of isolated technological breakthroughs. Instead, it is understood as a structural mechanism for exiting debt constraints, declining productivity, and prolonged stagnation—at the point where economies encounter the physical limits of existing systems.

This is why the focus of Davos 2026 discussions shifted decisively toward sectors that were traditionally considered “background” industries, but now define the ceiling of economic growth:

-

energy and power grids,

-

logistics and supply chains,

-

critical infrastructure,

-

industrial systems,

-

security and resilience.

Within this framework, energy ceases to be a supporting function. It becomes an infrastructure-driven growth factor that directly shapes the pace of development across all other sectors—particularly in an environment where AI and digital systems have moved beyond abstract “software” and have become scalable physical loads on grids, generation capacity, and infrastructure as a whole.

What Antonio Neri Emphasized: Sovereign AI, Physical Constraints, and a Path “From Within the System”

At Davos 2026, Antonio Neri, CEO of Hewlett Packard Enterprise, articulated a second framework—no less stringent in nature—an infrastructure-led one. In his public remarks within the WEF program and in closed sessions, he repeatedly underscored a central point:

“Geopolitics and AI are now inseparable.”

Governments and corporations are no longer deferring sovereign AI infrastructure to an undefined future.

The core implication of this position is that governments and large institutional actors are no longer discussing infrastructure in “someday” terms. Sovereign AI stacks are being built now, and the primary limiting factor is not the concept of AI itself, nor even compute capacity, but the physical realities of infrastructure:

power — availability and stability of energy,

cooling — thermal management and heat dissipation,

space — physical footprint and infrastructure density,

compliance — regulatory frameworks and control mechanisms.

Within this logic, it becomes clear that scaling AI is fundamentally an engineering and energy challenge, not a software abstraction.

Separately, Neri emphasized his personal career trajectory—not as an element of self-promotion, but as an explanation of long-term institutional development. He began his career at the company in a call center role in Amsterdam, and his progression to CEO was the result of sustained work within the system, belief in the company’s underlying architecture, and discipline maintained over decades. This path has been documented by Neri himself and in public sources.

For us, this is not a “motivational story.” It functions as an institutional metaphor:

infrastructure is built over long time horizons,

trust is established through consistency,

maturity is achieved through progression across stages,

and resilience is delivered by architecture, not by the volume of declarations.

Why This Context Was Relevant for Us

Within this framework, the context of the invitation becomes clearer. As the discussion shifts from what AI can do to what it physically runs on, attention inevitably turns to energy architecture—particularly in distributed and sovereign deployment scenarios.

HPE’s strategy, built around edge-to-cloud architectures, hybrid environments, and sovereign infrastructure, logically requires energy solutions that:

scale through distributed nodes rather than a single centralized core,

remain resilient under overload conditions and localized failures,

can be deployed close to the point of demand—at the edge,

and are managed as part of an integrated architecture rather than as isolated assets.

It is at this intersection that a space for alignment emerges. Our work does not treat generation as a standalone product, but energy as an architectural layer—one that enables distributed digital and AI systems to remain resilient within the real-world constraints of physical infrastructure.

In the Davos context, such convergence of frameworks is typically what gives rise to dialogue—not around finished solutions, but around the structural compatibility of approaches.

Why These Frameworks Converge at a Single Point: AI → Infrastructure → Energy → Architecture

Davos 2026 clearly marked a fundamental shift in the discourse among corporate leaders, public institutions, and investors: AI has moved beyond being a purely technological debate and has definitively entered the domain of infrastructure.

The conversation is no longer centered on model capabilities, compute platforms, or adoption speed. The central question has become the physical feasibility of scale—what AI actually runs on in the real world. Within this logic, nearly all discussions converged on a single constraint: energy and the grid.

The most consistent framework—repeated across statements by technology leaders, in executive briefings, and in closed discussions—was markedly pragmatic: the bottleneck for AI at scale is not algorithms or compute, but electrical capacity, access to the grid, interconnection timelines, and the ability of infrastructure to absorb growing loads.

This is why AI is increasingly described as the largest infrastructure build-out of the modern era—one with multi-decade horizons and capital intensity comparable to historical energy and transportation systems. In this build-out, energy is not a supporting component; it is the primary limiting factor.

A second shift occurred in parallel: the market moved from the phase of AI hype to the phase of AI ROI. Investors, boards of directors, and public authorities are asking less whether AI is needed and more how it is governed, measured, and integrated into existing accountability frameworks. This has intensified demand for solutions that are:

measurable and auditable,

governed at the process level rather than through demonstrations,

reliably deployable in industrial and public-sector environments,

compatible with regulatory and compliance requirements.

Once again, the focus returns to infrastructure: power, grids, resilience, and governance. Without these layers, AI ceases to be an asset and becomes a source of systemic risk.

A third reinforcing layer is geopolitical fragmentation. In a world where supply chain resilience and infrastructure autonomy directly affect the cost of capital, energy resilience has moved beyond ESG rhetoric and become a core element of national and corporate strategy. Resilience is now assessed not through declarations, but through system architecture.

As a result, the underlying logic of Davos 2026 crystallized into a simple but uncompromising sequence:

AI requires infrastructure,

infrastructure requires energy,

energy requires architecture,

architecture requires rules, standards, governance, and security.

At this point, the discussion ceases to be technological and becomes systemic.

The VENDOR.Energy™ Paradigm: Decentralization as a Mechanism of Resilience, Not an Ideology

We approach decentralization neither as a dilution of control nor as an opposition to centralized systems. In an infrastructure context, decentralization is an engineering instrument for reducing systemic risk—not a philosophical position.

What is required is a transition from fragile, hierarchical structures to topologically resilient networks of nodes, where the failure of a single element does not degrade the entire system. This approach has long been applied in telecommunications, distributed computing, and critical systems—and is now becoming necessary in energy infrastructure.

A properly designed decentralized architecture delivers properties that are critical for governments, corporations, and infrastructure investors:

localization of failures rather than system-wide cascading outages,

redundancy embedded in topology rather than added after the fact,

autonomous operation of individual zones under stress and crisis scenarios,

controllability, observability, and auditability instead of opaque “black boxes,”

the ability to define and enforce priority and access rules based on load scenarios and policy requirements.

A key principle often lost in public discussions is this: control is not synonymous with centralization.

In modern infrastructure, control is achieved not through a single central authority, but through verifiable coordination—a set of rules, protocols, and architectural constraints that allow a system to remain governable even when its structure is distributed.

This approach makes it possible to combine resilience, security, and scalability without reverting to the fragile monolithic models of the past.

Beyond BESS: Why Batteries Do Not Solve Architecture — and What Actually Does

In recent infrastructure discussions, Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) are often presented as a universal answer to resilience and flexibility challenges. We deliberately separate the usefulness of BESS as a component from the common misconception of BESS as an architectural solution.

BESS are important and will continue to play a role. However, by their nature, they address buffering—not system architecture.

5.1 Limitations of BESS as a Class of Solutions

In most standard configurations, modern BESS:

add an energy buffer that smooths load peaks and troughs,

do not alter network topology under typical integration models and therefore do not improve structural resilience at the system level,

do not eliminate architectural bottlenecks such as grid interconnections, power flows, localized overloads, or cascading failure scenarios,

inherit class-specific constraints, including predictable capacity degradation over time (typically to 70–80% of nominal capacity over 10 years), high unit capital intensity ($/kWh), dependence on global lithium-ion supply chains, and planned replacement cycles.

From a systems perspective, this leads to a clear conclusion: BESS improve the operability of an existing architecture, but they do not fundamentally increase its resilience. They operate within predefined constraints rather than removing those constraints.

5.2 From Linear Energy Systems to a Cellular Topology

The transition to resilient energy systems requires not an increase in the number of buffers, but a shift in architectural logic.

Instead of a linear model—center → distribution → consumer—a cellular topology is proposed, in which each object (a building, an industrial facility, or an infrastructure node) can function as an active energy cell.

In such an architecture:

resilience is formed at the level of topology, not solely through reserves,

balancing occurs not only through a central node, but via horizontal connections between cells,

local operating modes can be maintained autonomously when system-wide disruptions occur.

In our materials, this logic is described through:

local nodes (cells) as the fundamental unit,

a “honeycomb” connectivity model rather than a tree-like structure,

exchange and balancing as functions of architecture, not as external services provided by a central authority.

The key shift is that resilience becomes a property of structure, rather than the result of continuously adding reserves.

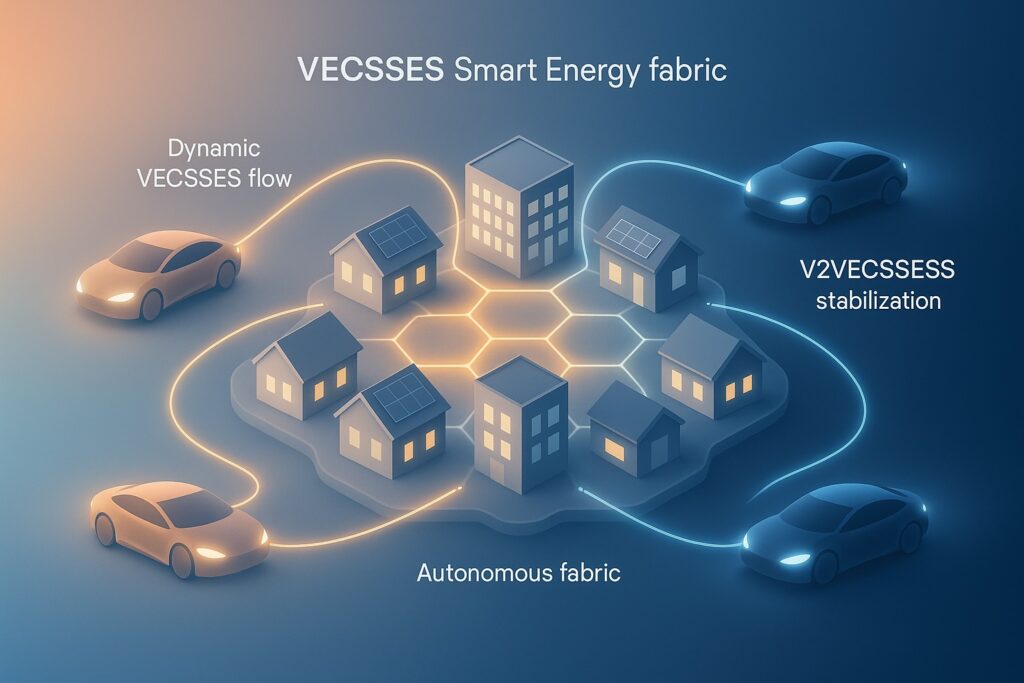

5.3 TESSLA as a Coordination Logic, VECSESS as an Energy “Cell”

In Data Room terms, this paradigm can be described as follows:

VECSESS is a module that makes an individual object energy-active—capable not only of consumption, but also of participating in local generation, stabilization, and exchange modes.

TESSLA is the coordination logic that connects such cells, ensuring their interoperability, regime compatibility, and stable operation of the network as a whole.

Crucially, within this model, energy ceases to be merely a physical flow. It becomes an architecturally managed parameter—embedded in the rules, protocols, and operating modes of the system.

This logic directly aligns with the core conclusion of Davos 2026: when AI and digital infrastructure require sovereign physical foundations and resilient operational contours, the winning models are not those that add yet another buffering layer, but those in which energy is designed into the system architecture from the outset.

How This Is Implemented in Practice: An Open Network of Nodes with VENDOR.Max as the Anchor Node

6.1 VENDOR.Max as an Infrastructure Anchor

In the proposed architecture, VENDOR.Max serves as a foundational infrastructure node—an anchor node—around which a predictable and controllable energy topology is formed.

Within this architectural model, VENDOR.Max is intended to function as:

a standardized node (a baseline architectural element),

a deployment anchor for building a distributed network,

a reference and test unit for modeling and reproducing operating regimes, load balancing behavior, power quality, and stress scenarios within validation and certification programs.

For institutional stakeholders, this distinction is critical: value is not created by a single device, but by a system that can be formally described, certified, controlled, and scaled without losing predictability.

6.2 Open Architecture: Integrating Any Energy Sources—Under Network Rules

The proposed architecture is designed from the outset (at the architectural design stage) to be interoperable. Third-party energy sources—diesel, gas, renewable, and others—can be integrated into the network, provided they meet a unified set of compatibility requirements.

Key conditions for inclusion in the network contour include:

Electrical Compatibility

Compliance with IEC 61000, EN 50160 (power quality), and IEEE 519 (harmonics); voltage tolerances (±10%) and frequency tolerances (±0.2 Hz); stable operating modes; and protection and power quality requirements agreed with the local grid operator.

Operational (Regime) Compatibility

The ability to operate under regulation, limitation, and prioritization scenarios, including flexible (“flex”) operating modes.

Correct Integration at a Specific Grid Connection Point

No phase imbalance, no degradation of power quality, no parasitic power flows, and no creation of localized overloads or infrastructure hot spots.

Observability and Controllability

Telemetry and monitoring as mandatory conditions for inclusion within the security, control, and audit perimeter.

Protocol Compatibility

The ability to be identified as a network element and to comply with access rules, limitations, and priority policies.

The underlying logic is straightforward and institutionally clear:

the objective is not to connect everything at any cost, but to ensure system resilience as the network scales.

This is not a closed ecosystem or a “walled garden.”

It is an open architecture with formalized rules, where compatibility and security are prerequisites for growth—not constraints on it.

Why This Model Is Becoming Foundational for Governments, Corporations, and Investors

Based on observations from Davos 2026, the concept of resilience has undergone a clear transformation. It has ceased to be an optional, ESG-decorative attribute and has become an operational metric within decision-making frameworks used by governments and large institutional investors.

Resilience is now treated as:

a parameter for assessing national security and energy sovereignty,

a determinant of industrial and technological competitiveness,

a factor influencing the cost and availability of capital, particularly for infrastructure projects,

a critical variable in the deployability of AI and digital infrastructure within mission-critical systems.

Under conditions of sovereign AI, geopolitical fragmentation, and rising infrastructure load, resilience can no longer be achieved solely through centralization or reserve capacity concentrated “at the core.” It requires an architectural response.

This is why a sustained demand is emerging for energy models that:

scale through distributed nodes, rather than single mega-projects,

are governed by protocols and formal rules, not ad-hoc manual exceptions,

withstand stress scenarios without cascading failures,

integrate with existing infrastructure rather than requiring full replacement,

create systemic resilience through topology, not through an oversized central hub.

For governments, this translates into reduced systemic risk and improved controllability of critical infrastructure.

For corporations, it provides predictability of deployment, regulatory compatibility, and protection of operational systems.

For investors, it offers lower volatility, clearer risk assessment, and long-term reproducibility of the model.

In this context, a decentralized yet protocol-governed energy architecture is no longer an alternative approach.

It is becoming a baseline infrastructure pattern for the next phase of digital and industrial transformation.

Looking Ahead

We are grateful for the level of dialogue made possible at USA House during Davos 2026.

This experience reaffirmed a practical reality articulated at Davos 2026 by leaders from Hewlett Packard Enterprise, USA House, and representatives of infrastructure capital: the global agenda is shifting toward a model in which energy, AI, and security are linked not by slogans, but by infrastructure physics. In this model, the decisive factor is no longer power capacity in isolation, but architecture—architecture capable of delivering resilience, controllability, and scalable performance over the long term.

For us, this serves as confirmation of the direction we have chosen: approaching energy as an architectural challenge, where resilience is not achieved through isolated solutions, but through topology, formal rules, and coordinated interaction among nodes.

We remain open to dialogue and collaboration worldwide—with industrial companies, research institutions, government bodies, and technology partners. The development of critical infrastructure requires broad, multi-layered cooperation and shared engineering responsibility.

Contact

For discussions related to partnerships, pilot projects, research programs, or infrastructure initiatives, please use the contact channels provided on this website.

Disclaimer

Participation in the Champions of Innovation event does not imply endorsement, partnership, inclusion in official programs, or the existence of any commercial agreements with Hewlett Packard Enterprise, USA House, the U.S. Department of Commerce, or any individuals referenced. The views expressed in this material represent solely the position of VENDOR.Energy and are based on public statements and open discussions held during Davos 2026.